Chicago’s Taste of America | Image:Pininterest

Hot properties. The Great Fire of London started in a bakery. Thomas Farriner, the establishment’s hapless owner, said later that he thought he had extinguished the flames. Hours later, the inferno was snaking through the city at a terrifying pace. More than three centuries on, something similar is happening in U.S. commercial property as discrete plumes of smoke threaten to turn into a conflagration. Investors will get burned, but the damage can still be contained.

A few lenders are already getting singed. Last week, a listed real estate fund managed by KKR cut its dividend after recording a loss on a Philadelphia office loan. Mid-sized lender New York Community Bancorp earlier took a large charge against loans secured by properties, and its shares collapsed. The flames have also licked their way across the ocean: Shares in Japan’s Aozora Bank and Germany’s Deutsche Pfandbriefbank plunged after forecasting losses on U.S. real estate lending.

The underlying cause of these problems is the rapid rise in interest rates over the past two years, which pushes down the value of property by making future rental income relatively less appealing. The trouble started with office property, which underpins around a quarter of all U.S. commercial real estate mortgages according to Morgan Stanley. It has the extra problem of workforces only partly returning to their desks, leading tenants to downsize and constraining landlords’ ability to crank up rents.

But what started in offices is now spreading to so-called multi-family properties such as apartment buildings. There’s no shortage of demand overall: families still need somewhere to live. Even so, the combination of higher rates and the difficulty in getting tenants to pay more can create problems. NYCB’s setback stemmed partly from New York apartments affected by government curbs on raising rents. Some cities in the southern “sunbelt” have aggressively built new supply.

The bigger challenge is that the wave of mortgages coming due could turn a micro problem into a macro one. Borrowers are due to repay $929 billion of U.S. commercial real estate loans this year, and $573 billion the year after, according to the Mortgage Bankers Association. Of this year’s haul, almost one-third appears to be loans due last year where borrowers have renegotiated or delayed repayment. And one-third of the total amount coming due is backed by multi-family properties.

The math is not encouraging. Consider the owner of a $100 million office building who borrowed 60% of its value three years ago, only to see its price slump by half. The borrower owes $60 million but might only be able to raise half that sum in a new loan secured by the same property. Fitch Ratings estimates around half of loans parceled up into U.S. commercial mortgage-backed securities could be unable to refinance.

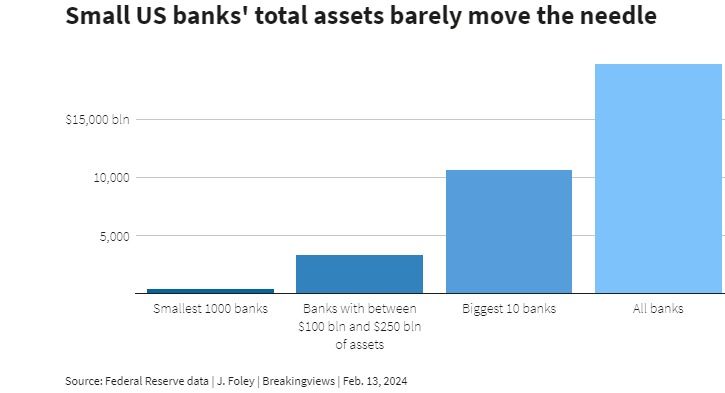

Locating the problem is tricky, but in broad terms small U.S. banks are the worry. Non-residential real estate makes up around one-third of loans at American banks with balance sheets smaller than $100 billion, but only 8% at institutions above that threshold, based on quarterly regulatory reports. For those smaller banks, non-residential commercial property loans are equivalent to roughly twice the lenders’ Tier One equity, the shock-absorbing part of a bank’s balance sheet. For the biggest institutions, the same exposures are less than 50% of their capital. Unsurprisingly, banks are dramatically reining in new commercial-property lending.

One red flag for regulators is banks which have commercial real estate exposures worth more than three times their equity. Even then, some will be highly diversified, while others are not. Since lenders don’t itemize their loans publicly, investors make assumptions. Valley National Bancorp, a New Jersey-based lender, has commercial real estate loans equivalent to four times its equity. They’re individually small and spread out, yet the bank’s share price has fallen by a quarter this year.

Much like the residents of London in 1666, lenders and borrowers will try to put out small fires however they can. Banks often renegotiate loans to help borrowers avoid default. In some cases, non-bank sources of capital, like private credit funds, will plug holes in the refinancing wall. That’s more true for multi-family properties, where borrowers may just need a couple of years of funding to tide them over before valuations recover. Even then, private lenders can be picky, and pricy. Loans can come with a mid-teens interest rate, investors say.

For troubled office owners who can’t strike deals with opportunistic capital providers, and some multi-family owners too, default will loom, and banks’ balance sheets will feel the effect. That’s likely to accelerate the thinning of the undergrowth in the U.S. financial system. There are still more than 2,000 banks in the United States. Scott Rechler, CEO of real estate investor RXR and a director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, estimates up to 1,000 could disappear within the next two years.

In the abstract, wiping out a few hundred smaller lenders may sound fine. In practice, it could cause chaos. If 500 failed, it would be ten times more institutions than U.S. regulators – who already gripe about being understaffed – have wound up over the entire past decade. After the collapse of SVB Financial last March, investors and depositors fled from banks with similar characteristics, in a reminder that bank failure can be driven more by rumor and geographical adjacency than actual credit losses.

If interest rates come down rapidly, the problem could abate – at least for multi-family properties. If not, there’s time to prepare for the worst. Banks are already laying aside provisions to cover bad debts, but bank supervisors may push them to do more, even if equity investors like NYCB’s don’t like the result. That might include encouraging them to sell troubled loans, which many institutions are loathe to do since it forces them to crystallize their losses.

There’s also time for regulators to be clear about the fact that some banks might still fail, and that’s okay. Even that signaling could precipitate problems for some lenders and push others into mergers with larger and stronger rivals. That is not necessarily a bad thing, though. Back in 17th Century London, the Great Fire stopped after Londoners blew up some houses in the blaze’s path to curtail its spread. The coming conflagration could benefit from a similar approach.